Chad Schwitters, Communities senior program officer, heard a disturbing theme from his conversations with grantees during 2023 – the affordable rental portfolios held by nonprofit housing organizations, especially those providing supportive housing, were getting more and more economically precarious. Costs had significantly changed since they put together the financial projections that enabled them to get tax credits, and the lack of funding for maintenance, security, and insurance was threatening their ability to continue operating.

“The mental health crisis, the opioid epidemic, and the aftershocks of the pandemic economy hit communities very hard, which has hit the residents our organizations serve very hard, which then hits us very hard.”

–CHRIS LaTONDRESSE, PRESIDENT & CEO, BEACON INTERFAITH HOUSING

This development was troubling. For some of the most vulnerable people in Minnesota – people experiencing mental illness, chronic health conditions, and histories of trauma – a stable home can be foundational in securing treatment and working toward recovery and healing. Supportive housing combines rental housing with coordinated services that support residents in improving their quality of life, at rents they can afford. It’s an important part of Minnesota’s housing puzzle. If supportive housing providers couldn’t secure adequate funding, Minnesota’s homelessness crisis would likely deepen, moving more people into unstable housing situations.

“The mental health crisis, the opioid epidemic, and the aftershocks of the pandemic economy hit communities very hard, which has hit the residents our organizations serve very hard, which then hits us very hard,” said Chris LaTondresse, president & CEO of Beacon Interfaith Housing Collaborative, a collaborative of congregations committed to making sure all people have a home. “Operationally, it’s translated into increased operational complexity, stacked on razor-thin margins and old assumptions about the cost of doing business, for supportive housing in particular.”

We held conversations with grantees in 2023, while the state of Minnesota was appropriating a record $1 billion to support affordable housing – more than 20 times the spending in a typical two-year budget – out of the state’s $17.5 billion surplus that year. The new funding was intended to build more affordable apartments, help low-and moderate-income people buy their first homes, and provide rental assistance to thousands of households. Additionally, a new quarter-cent sales tax in the seven-county Twin Cities metropolitan area – the first of its kind in the state – would raise an additional $250 million between 2023 and 2024 to fund affordable housing development and homelessness prevention in the region.

There was one problem: policies or investments targeted to preserve existing housing or to provide adequate resourcing for supportive housing were woefully inadequate. This was a system-wide issue that could result in the loss of a lot of affordable housing units in the region. As one of the largest housing funders in Minnesota, we knew that McKnight had a responsibility to do something about it.

Working alongside the Family Housing Fund, Greater Minnesota Housing Fund, Local Initiative Support Corporation (LISC), and Metropolitan Consortium of Community Developers (MCCD), we convened conversations to explore how philanthropy could support housing providers. Providers were initially nervous about participating; they didn’t want to speak openly about their economic challenges, fearing risks to their reputations and retaliation from lenders and public funders. The challenges were acute, however, with some believing that selling off housing units was the only way for their organizations to continue operating.

“Chad was willing to listen to those of us in the field when we reached a crisis moment locally. He listened when we asked,’Can you help us?’”

–WILL DELANEY, INTERIM EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR & ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR, HOPE COMMUNITY

After a few more conversations, stakeholders eventually organized themselves into work groups to recommend tangible solutions that could be achieved through administrative change, policy change, emergency funding investment, and coordinated entry reform to better manage intake, assessment, and provision of referrals. This working group is now known as the Minnesota Housing Stability Coalition and is being managed and staffed by the Family Housing Fund, a nonprofit housing intermediary and McKnight partner that works across sectors to meet affordable housing needs in the Twin Cities region.

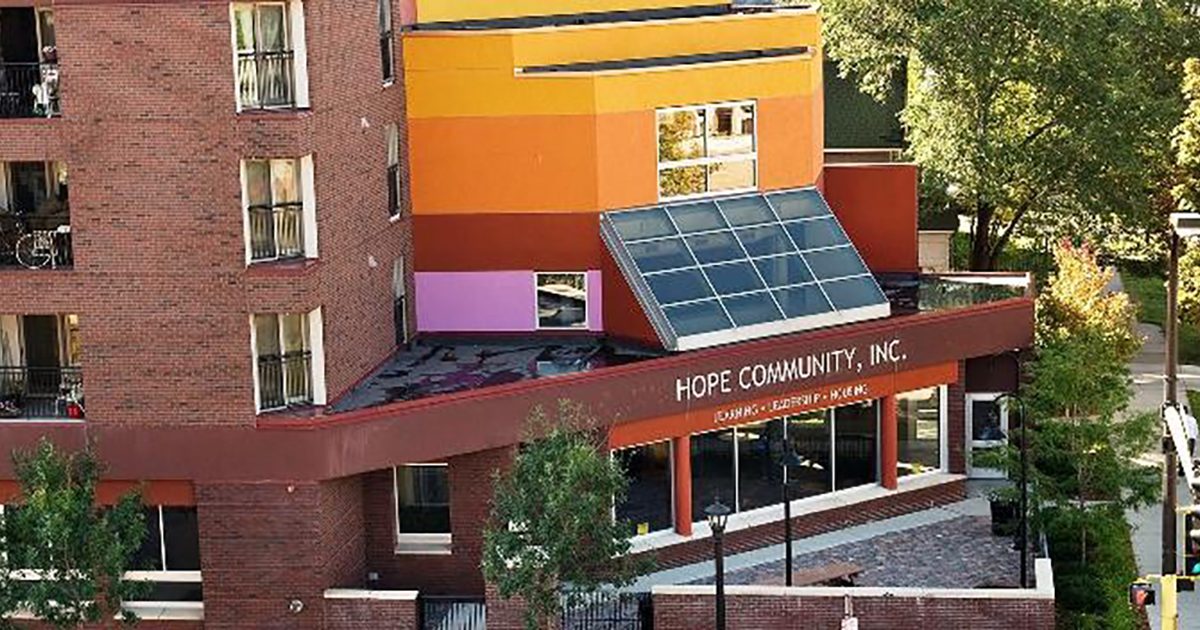

“Chad was willing to listen to those of us in the field when we reached a crisis moment locally,” said Will Delaney, interim co-executive director of Hope Community, a nonprofit organization that uses deep listening and community organizing to work at the intersection of people and place in the Phillips neighborhood of Minneapolis. “He listened when we asked, ‘Can you help us?’”

After a few more conversations, stakeholders eventually organized themselves into work groups to recommend tangible solutions that could be achieved through administrative change, policy change, emergency funding investment, and coordinated entry reform to better manage intake, assessment, and provision of referrals. This working group is now known as the Minnesota Housing Stabilization Coalition and is being managed and staffed by the Family Housing Fund, a nonprofit housing intermediary and McKnight partner that works across sectors to meet affordable housing needs in the Twin Cities region.

“There’s no way we can have a vibrant affordable housing community without philanthropic support. McKnight is, to me, a leader from the philanthropic side because of their history, scale, and willingness to convene conversations when they need to come up. They encourage innovation and relationship building. Funders talk about providing assistance beyond dollars; McKnight actually does that.”

–WILL DELANEY, INTERIM CO-EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, HOPE COMMUNITY

“The Minnesota Housing Stabilization Coalition has been a powerful vehicle to articulate the problem we’re trying to solve for – like, ‘oh, this happening to you too?’” said Ellen Sahli, president of the Family Housing Fund. “It’s not organizations falling down on the job in their own individual ways. It’s a systems challenge that requires a systemic response.”

McKnight could have allocated additional grants to each housing provider to address what were initially perceived as individual crises, but this approach wouldn’t have addressed systemic challenges, nor to changes that could prevent future crises. McKnight didn’t simply act as a funder; it used its convening power to respond to what was emerging and foster collaborations among people with the power to advance solutions. This will help create the conditions for long-term systems change, ultimately keeping more people housed in Minnesota for the long haul.

“There’s no way we can have a vibrant affordable housing community without philanthropic support,” said Will. “McKnight is, to me, a leader from the philanthropic side because of their history, scale, and willingness to convene conversations when they need to come up. They encourage innovation and relationship building. Funders talk about providing assistance beyond dollars; McKnight actually does that.”