David Mura is a Minnesota-based memoirist, essayist, novelist, poet, critic, playwright, and performance artist.

His memoirs, poems, essays, plays, and performances have won wide critical praise and numerous awards. Their topics range from contemporary Japan to the legacy of the internment camps and the history of Japanese Americans to critical explorations of an increasingly diverse America.

Mura recently turned in his next book, a collection of essays on Asian American identity and his life as a practicing artist. The book, tentatively titled Goodbye, Miss Saigon, is expected to be published in the spring of 2026.

Arts & Culture Program office Bao Phi shared, “David Mura’s accomplishments are many. But what may not show up on paper is how he set a tone of selfless, community-forward, community-engaged artistic practice for decades in Minnesota, and how much of a mentor and role model he has been in laying a pathway for the next generation of artists.”

In this interview, David shares his vision for a future where equality, freedom, and democracy are not just goals, but a reality, and the role of artists in shaping that future.

INTERVIEW

McKnight: What future are you working to build?

David Mura: In my recent book, The Stories Whiteness Tells Itself: Racial Myths and Our American Narratives, I write:

From its very beginnings America had two irreconcilable goals. One was to seek equality, freedom, and democracy. The other was to maintain white supremacy and the domination by white people over any people of color. White America is fine with telling our tale through the lens of the first goal. But it is still decidedly not fine with telling the second story of America’s treatment of people of color and America’s desire to maintain white supremacy.

As an Asian American writer my work has centered on telling this second story. And ever since I read Baldwin’s The Devil Finds Work in my late twenties, I’ve understood that I’ve had to educate myself in the myriad communities, histories and cultures that are so often omitted or relegated to the margins by the mainstream white culture.

I firmly believe that the pursuit of equality, freedom and democracy is intricately tied to the work of artists. In his study of culture in the post-civil rights era, Who We Be, Jeff Chang lays out the importance of culture in political change:

Here is where artists and those who work and play in the culture enter. They help people to see what cannot yet be seen, hear the unheard, tell the untold. They make change feel not just possible, but inevitable. Every moment of major social change requires a collective leap of imagination. Change presents itself not only in spontaneous and organized expressions of unrest and risk, but in explosions of mass creativity.

So those interested in transforming society might assert: cultural change always precedes political change. Put another way, political change is the last manifestation of cultural shifts that have already occurred.

In 2021, Carolyn Holbrook and I co-edited We Are Meant to Rise: Voices for Justice from Minneapolis to the World, an anthology of Minnesota BIPOC writers. This anthology gives a very different picture of Minnesota than Garrison Keilor’s Lake Wobegon. Even more importantly, the creativity, power and witness of these BIPOC writers attest to Chang’s premise that cultural change precedes political change. A number of the essays center on the police murder of George Floyd and the demonstrations here in Minnesota which were then echoed not just nationally but around the world.

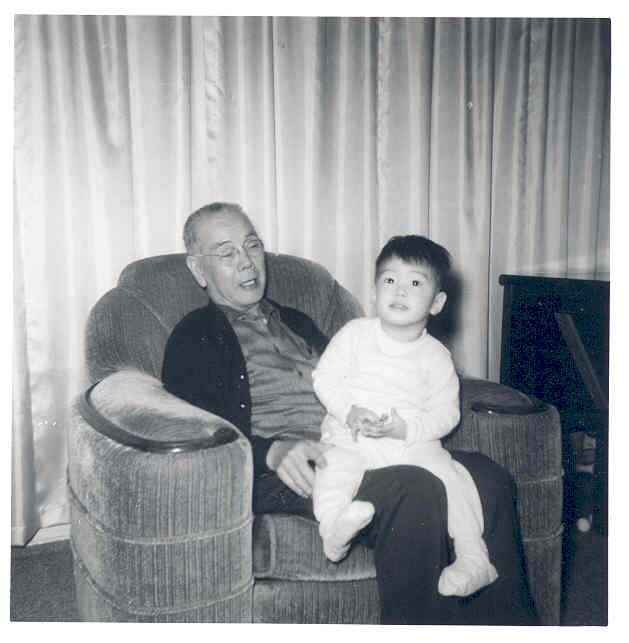

In the anthology, I write about the TPT documentary, Armed With Language, that I co-produced, wrote and narrated. It tells the story of the second generation Japanese Americans—Nisei–who served in the Military Intelligence Service in WWII and were trained at Fort Snelling. Many of these soldiers were recruited from the prison camps where the US government incarcerated 120,000 Japanese Americans, including my parents. MacArthur’s chief of intelligence, General Willoughby, claimed that these Japanese American soldiers shortened the war in Pacific by two years and saved a million American lives. And though their contributions are still mainly unrecognized, what the story of the MIS Nisei illustrates ought to be obvious: Our diversity is a strength, not a weakness.

At 71, I am still working for a future America we have yet to see—one where equality, freedom and democracy are not just a goal, but a reality.

“I firmly believe that the pursuit of equality, freedom and democracy is intricately tied to the work of artists.”– DAVID MURA

McKnight: What or who inspires you to act?

David Mura: Both my parents passed in the last two years, and their deaths have spurred me back into writing about our family’s past and Japanese American history. Though my parents tended to minimize or avoid speaking about their childhoods and their incarceration by the US government, in their last couple years they began to speak more about their past. As the oldest member now in my extended family, I realize I am now a keeper of our history.

Recently, at the Associated Writing Programs conference, I had an inspiring conversation with the brilliant MN writer Shannon Gibney about Robin Coste Lewis and her book To the Realization of Perfect Happiness, which pairs poetic texts with her grandmother’s photographs. Looking at that book, I realized that all my family photos are now historical documents. Here’s what Shannon wrote on her FB about our conversation:

David and I were talking about artifacts you find of your family(ies) as you age (if you’re lucky), and then you realize those stories and experiences will die unless you, the writer, decide to work with them in some way. I was also reminded of Bao Phi’s observation that creative writers from historically marginalized communities are often the first historians our people have, as mainstream dominant culture usually has little interest or investment in our stories. And will approach them with a different, often problematic perspective.

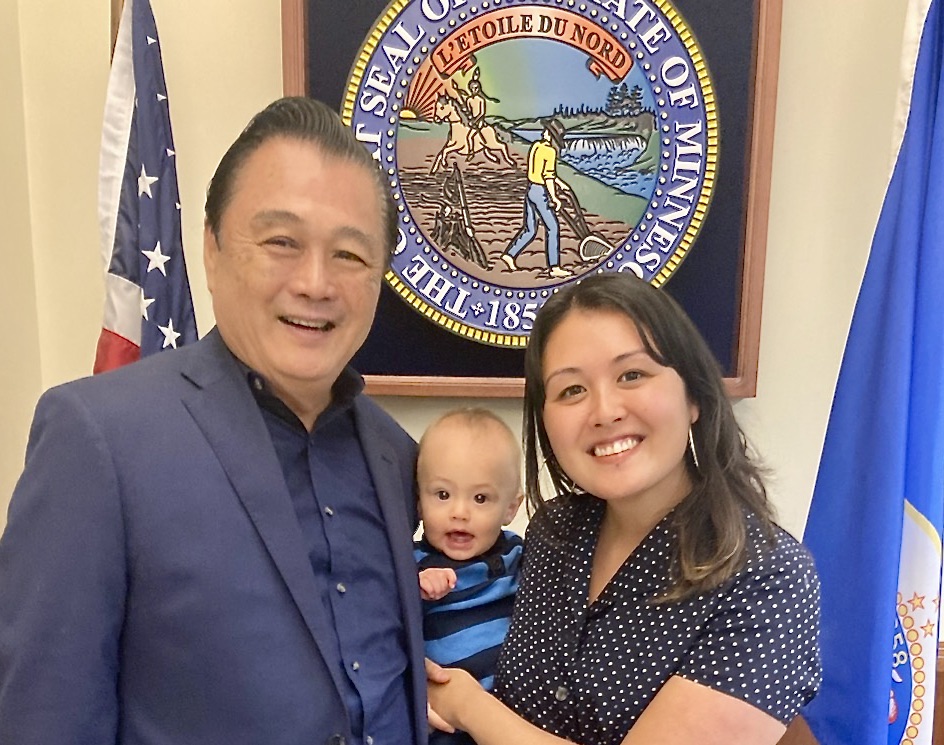

As another signal in the passing of generations, two years ago my grandson Tadashi was born, and he’s named after my uncle who was one of the MIS Nisei. In 2022, after serving as the director of 826 Minneapolis, a creative writing and tutoring organization for marginalized students, my daughter Samantha, was elected to the MN House of Representatives from South Minneapolis. She sponsored the ethnic studies bill which passed last year by saying, “When my father was growing up, he didn’t learn about the Japanese American internment in school and neither did I. I want my son to be able to learn about that history and the history of other BIPOC communities in his school.” My daughter’s activism and my grandson’s future—they too are my inspiration.

In The Stories Whiteness Tells Itself, I quote from a op ed letter a Northside teacher, Olivia Rodriquez wrote shortly after the murder of George Floyd. She had asked her class to write a piece about “My America”:

Nearly 100% of my class wrote about their fear of police and police brutality. In seventh-grade words, they expressed unjust behaviors by authorities towards them. They are 12 and 13 years old. They do not need this weight on their shoulders right now. Their goals should be learning and being a kid. I sat down at my desk and sobbed thinking of what my students go through on a daily basis while they are walking, playing and talking while black. My students are funny, smart, worldly, wise, creative, loving, caring, generous, and independent young people…Right now, they do not feel safe. As a young white child in St. Paul, I felt the police were there to protect me. My students have never felt that. This needs to change.

The still denied truth about America’s racism is frighteningly clear to BIPOC young people. In so many ways I am writing more for them and their future, than to those of my own generation. We have to do better by them, and part of this should involve more arts in the schools and organizations like TruArtSpeaks, 826 MSP and Alexs Pate’s The Innocent Classroom, rather than the many cuts for arts education and the backlash against diversity we’ve seen in recent years.

“ I don’t think I could find anywhere in America where I could be a part of such a diverse and activist and collaborative artistic community.”– DAVID MURA

McKnight: What do you love about Minnesota, your community, and your people?

David Mura: When I came to the Twin Cities in 1974, it seemed to me and others to be a very white place; though there were significant Black and Native American neighborhoods here, the mainstream white culture did not recognize their existence, much less their artistic voices. Since that time, there’s been wave after wave of immigrants—Southeast Asian refugees (Vietnamese, Hmong, Laotian, Cambodian), East Africans (Somali, Ethiopian, Eritrean), a whole influx of Mexican and South American immigrants, Liberians, Karin, Bosnians, Tibetans, South Asians. From these populations more and more artists have come to maturity. The diversity here has shaped the lives of my children, their sense of what America is. And it has shaped my own writing and artistic vision.

In the early 1990’s I helped start the Asian American Renaissance, a community based arts organization; Theater Mu started at the same time and is now the second largest Asian American theater company. We have such an activist Asian American artistic community here; we’re the only such community which protested Miss Saigon with such tactical planning and force that we got the Ordway Theater to apologize and promise never to bring back this egregious grab bag of racism, Orientalism and colonial ideology.

That work was typical of the activist and artistic communities here. The Coalition of Asian American Leaders has fostered a new generation of AA leaders. I was for a time part of Pangea World Theater, which is now an established presence in our community. I’ve been on the board of the Ananya Dance Theater, and I like to tell people we have three nationally known Indian based dance troupes here–not necessarily an expected phenomenon in the upper Midwest. Penumbra is a national treasure where the great August Wilson got his start. The Loft and the Playwright’s center have fostered an amazing literary community, along with the small presses, Graywolf, Coffee House and Milkweed, and Carolyn Holbrook’s S.A.S.E. and More Than a Single Story. And of course all this has been nurtured by the support for the arts here, from foundations like McKnight and the Jerome, where I served on the board, to corporate and government funding.

I won’t list all my amazing artistic friends here because I’ll leave someone out. But I don’t think I could find anywhere in America where I could be a part of such a diverse and activist and collaborative artistic community, and that is one of the reasons, other than my children, that I stay here.