When two-year-old Sambath “Sam” Ouk and his family escaped the killing fields of Cambodia and arrived in Rochester, Minnesota, in the early 1980s, they became part of the first large wave of Southeast Asian refugees to resettle in the state.

During his early years in Minnesota, Ouk struggled to figure out where he fit in between two radically different cultures and places. At home he spoke Khmer with his family, but once he stepped outside his front door, he found himself in an unfamiliar world.

“I was a child growing up without a nation,” he says. “This struggle to belong somewhere played a big part in the lives of myself, my uncle, my aunt, and our friends growing up together in a refugee community.”

“My teachers empowered me. I wasn’t alone as I navigated the two worlds of the refugee and American student experience.”—SAM OUK, ENGLISH LEARNER COORDINATOR, FARIBAULT PUBLIC SCHOOLS

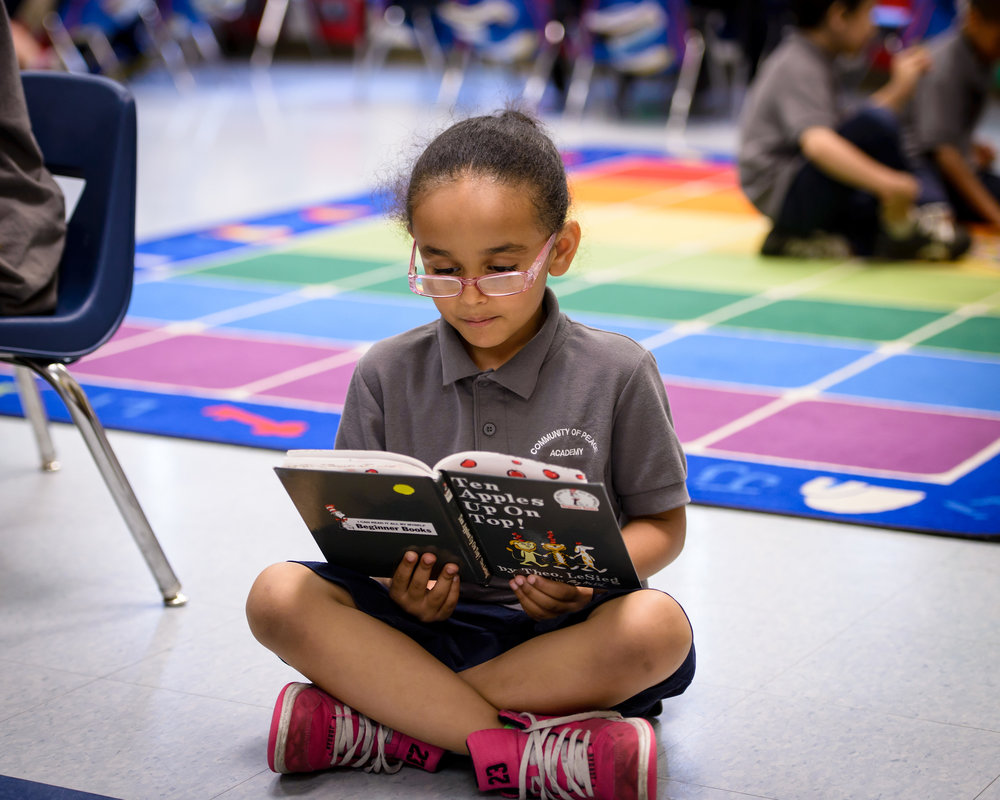

School helped alleviate that stress. He learned how to speak English and started to feel like he belonged somewhere. “If I never learned the words or found my own voice, America would have just felt like another refugee camp,” he says. “Fortunately for me, my English as a Second Language (ESL) classes taught me the words, and I was able to find my voice.”

His teachers encouraged him to learn about his Cambodian culture and to share it with his English-speaking classmates. “My teachers empowered me,” he says. “Even after I exited the program, I would go back to my ESL teachers and they provided strong guidance for me. I wasn’t alone as I navigated the two worlds of the refugee and American student experience.”

The Newest Challenge, The Newest Opportunity

Today, there are around 230,000 school-aged children from immigrant families in Minnesota — that’s a 60% increase since 2000.

Some of these children, like Sam Ouk, came to the United States at a young age, but many were born here. Collectively, they speak nearly 200 languages and enter school with a wide range of academic preparation. Some are bilingual children of highly educated parents while others arrive in Minnesota with no formal education and speak only their native language.

Immigrants add tremendous value to our state’s social, cultural and economic vitality. They pay more than $1 billion in state and local taxes and contribute nearly $9 billion to the state’s economy.

Their children are Minnesota’s next generation of leaders and citizens. This budding labor force will become especially critical as demographers anticipate a dramatic increase in the number of baby boomers retiring.

How prepared our children will be to lead tomorrow hinges on how well we educate them today.

“It’s the newest challenge for the school systems, and it’s also the newest opportunity to strengthen Minnesota,” says Delia Pompa, senior fellow for education policy at the Migration Policy Institute. “It all starts in the schools. If we don’t do this well, eventually it will impact how the state does overall.”

How prepared our children will be to lead tomorrow hinges on how well we educate them today.

Lifting Up the Voices of Parents, Educators and Community Organizers

Inspired by his public school experience, Ouk pursued an education minor in college before earning his teaching license and master’s degree in ESL.

“We are ensuring the voice of the people who are most impacted by the policies.”—BO THAO-URABE, COALITION OF ASIAN AMERICAN LEADERS

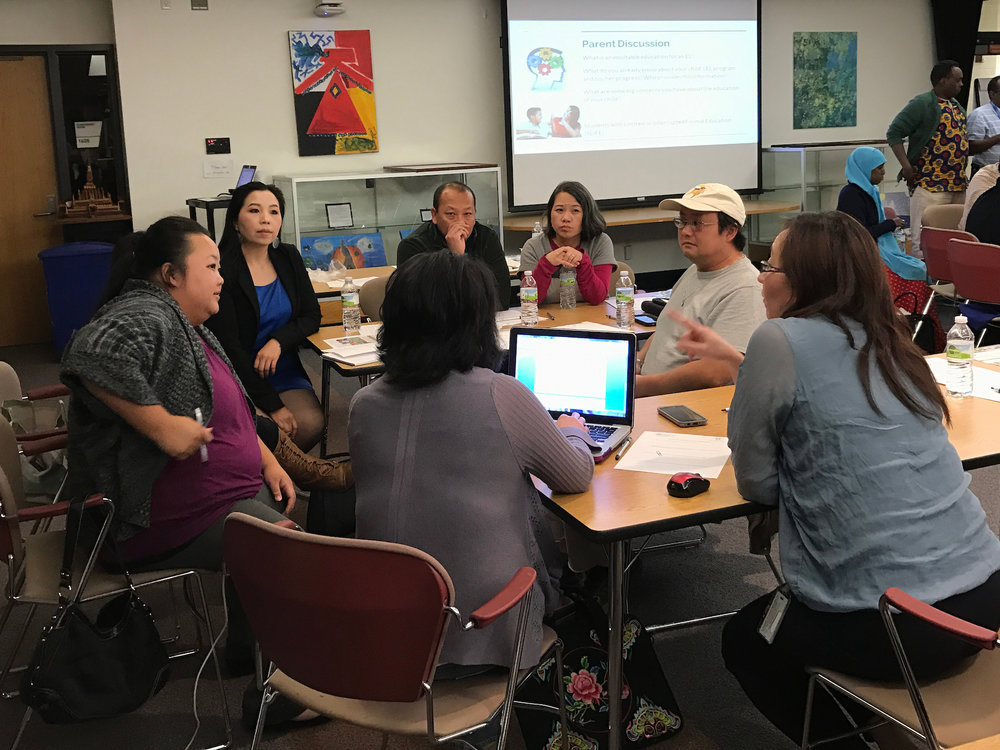

Today he works as an English Learner coordinator for Faribault Public Schools. Over the past year, he’s worked with the Coalition of Asian American Leaders (CAAL) on an effort funded by The McKnight Foundation’s Education and Learning program to ensure that all multilingual children are supported as well as he was. To do that, CAAL engages parents, educators, and community organizations to recommend changes that would help the Minnesota Department of Education better identify and meet the needs of children who require language services. “What we’re doing is regrounding the opportunity,” says Bo Thao-Urabe, CAAL’s network director. “We are ensuring the voice of the people who are most impacted by the policies.”

CAAL’s perspectives come at a critical time as Minnesota develops its plan to meet the requirements of the new Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) before it goes into effect for the 2017-18 school year. ESSA, which replaces the No Child Left Behind Act, determines how the federal government holds states accountable for boosting academic achievement at all schools, especially high-poverty schools. For the first time, significant weight will be tied to how schools improve the English language proficiency of students who aren’t native speakers.

“One objective is to make sure the education system is much more transparent. We want parents to understand the system well enough to advocate for their children.”—KAYING YANG, COALITION OF ASIAN AMERICAN LEADERS

To make sure parents and educators stay informed as ESSA evolves, local community leaders explained the changes to ESSA on Hmong and Spanish TV and radio stations. CAAL and the Minnesota Education Equity Partnership also facilitated parent meetings and brought stakeholders together, including teachers, school administrators, university researchers, parents, and advocates from different ethnic communities. “One objective is to make sure the education system is much more transparent,” says KaYing Yang, policy director at CAAL. “We want parents to understand the system well enough to advocate for their children.”

This also includes outreach to multilingual communities beyond the Minneapolis-St. Paul metro area. With CAAL’s help, Ouk brought families, teachers, legislators, and community leaders together to talk about the issues. “Instead of inviting just one or two of us to go to the Twin Cities, we brought the Twin Cities here to demonstrate what we’re doing,” says Ouk.

Efforts like these give policymakers a window into the real-life experiences of students and families, which they need to better understand as they try to address the urgent task of educating the increasing number of children from immigrant or refugee families.

“The refugee experience ends when the refugee finds a place that they can call home again,” says Ouk. For this Cambodian refugee, school was the place where he learned English, and more importantly, it’s where he found his voice. And that’s a gift Ouk and other educators hope to pass on to the next generation of students.